How Many Cups 32: Neil Gorsuch & Company Time Travel To 1866, And The Criminal Future Of Homelessness

the door for convict-leasing is suddenly open again

As Much Coffee As Needed To Stay Awake

For my 30th birthday, my favorite sister bought me a brick. It lays just outside our picturesque town hall, reading “something yet to learn.” A few yard from it sits a bench that both my perfectly sculpted dumpy and nonfiction books are no stranger to.

It is where I first read Eric Foner, the world’s preeminent historian on 19th Century American racism. After 45 minutes of reading or so, I usually fight off the temptation to take a little snoozer, but not while reading Foner. His retelling of Jim Crow vagrancy laws serves as a reminder of just how cruel humans can be, jolting the mind awake as it races through more existential thoughts.

A summer ruling from the Supreme Court has me thinking about these laws once more. An empathetic mind will wonder if the nation is turning their backs on those most in need. A cynical one will wonder who stands to gain from it.

“In most or perhaps rather in many cases the farmers have not the means at command, to pay wages monthly; but are willing to work the land on shares or secure partial deferred payments”

- Freedmen's Bureau Assistant Superintendent for Princess Anne County, Virginia,

Hardly discussed in history classes is what happened immediately after The Civil War. What occurs when over four million people leave plantations and enter the free labor market? How can a nation provide both housing and jobs in such an unprecedented crisis?

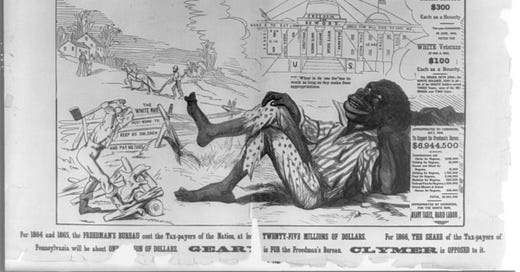

To address this issue, The Freedmen’s Bureau was created. Its goal was to provide a range of assistance to former slaves, including housing, healthcare, labor disputes with plantation owners and overall employment. As quotes like the one heading this section denoted, freedmen wanted nothing more than to prove their worth by making a living.

Still, many Blacks struggled to be gainfully employed, largely due to a form a purposeful discrimination. Plantation owners either did not want to pay Black folks or did not have the means to. Consider White farmer W.K Lowery: “I have kept these Freedmen since the 9th of April 1865 at my own expense, (as well as all time before), with the exception of a few rations furnished by the Bureau which were so indifferent that they could not be used, not being able, as well as not inclined to keep them any longer.”

Lowery turned these men over to the care of The Freedmen’s Bureau, who often did not have the means to care for them themselves. Naturally, homelessness and joblessness rose in tandem. Wealthy and opportunistic Whites saw this as a potential advantage. Could freed Blacks be legislated into forced labor if they were caught without a job?

Virginia’s Vagrancy Act of 1866- soon to be mimicked my other states - turned this dream into a reality. It mandated that if someone was caught unemployed or homeless, they would be punished with up to three months of forced servitude in some Virginia prison. Those folks would be paid wages if an employer would have then, but such instances were markedly rare.

More common were two different paths. Sensing this scheme as Slavery 2.0, many freedmen and women chose to flee their employer. If caught, they would be shackled with a ball and chain and forced to work for free. If no employer wanted them at all then vagrants were forced into completing public works projects, also with no pay. What’s more, states would often sell vagrants to employers, known as convict-leasing. Mississippi’s Black Codes, unsurprisingly, best demonstrate this practice.

“All freedmen, free negroes and mulattoes in this State, over the age of eighteen years, found on the second Monday in January, 1866, or thereafter, with no lawful employment or business…shall be fined in a sum not exceeding, in the case of a freedman, free negro or mulatto, fifty dollars.”

- Mississippi Vagrant Law of 1866

And if such a fine could not be paid then the vagrant would be leased out to an employer. They would work for the employer until the fine could be paid off. As your intuition is rightfully telling you, such wages were not always given in good faith, often held back on accusations of laziness or a job left incomplete.

A quick aside: there was more than one way for White employers to squeeze out state-induced free labor. Black orphans and children of vagrants were, by law, sent into apprenticeships. Employers could reap years of free labor and even deliver punishments to their apprentices.

Another quick aside: The state of Texas extended this law to apply to the family members of vagrants. Former slave Harriet Anthony was forced to work in a chain gang while pregnant, eventually leading to a miscarriage of both unborn child and justice.

In sum, the 13th Amendment made slavery clearly illegal, with the exception of forced labor impressed upon criminals. Therefore, White legislators and employers invented a way to criminalize Blacks (via homelessness and unemployment) and send them into a world not far removed from slavery.

Although they may have transformed into the term loitering, vagrancy laws extended well into the 20th Century. Indeed, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr was arrested on loitering charges during his famous Selma demonstration and such tactics were used against the Hippies of the Sixties. Today, it may be on the verge of a comeback.

“Instead, the majority focuses almost exclusively on the needs of local governments and leaves the most vulnerable in our society with an impossible choice: Either stay awake or be arrested.”

- Justice Sonia Sotomayor

Recently, the Supreme Court took a case concerning both the 8th Amendment and homeless peoples. A group of homeless folks took legal action against the city council president of Grants Pass, Oregon, Lily Morgan, who attempted to stop them from sleeping in public places.

Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote for the majority that it was indeed not “cruel or unusual” for municipalities or states to either fine or arrest homeless folks encamped in public spaces. Pair that with Morgan’s statement about her policy: “the point is to make it uncomfortable enough for in our city so they will want to move on down the road.”

This isn’t a blog about homelessness, although it could be. Coincidentally, I happened to blackout for a moment and apparently my fingers typed the random, completely unrelated set of facts below:

There are more vacant homes than homeless people, by millions.

111,620 children were homeless last year.

They all want homes.

None of them are responsible for not having a home.

Between 40-60 percent of homeless people have jobs but can’t afford housing.

14 to 21 percent of the homeless have been victims of violent crimes.

I’m of the belief that nobody wants to be homeless and most people slip into it unexpectedly. Once there, they often lack the requisite materials - phones, access to hygiene, reliable transportation - to land a job and purchase housing. Those with a job are dueling against inflation and competing tenants. I became of this belief not because I am some bleeding liberal but because I read Matthew Desmond’s award winning Evicted, of which I have two copies and am willing to loan one out.

“Be must take care, lest borne away by a torrent of passion we make shipwreck of conscience.”

- John Adams

But here is my point.

Homelessness has done more to reveal the limits of the American heart than the magnanimity of it. The narrative around poverty, both dinner-table and legal, has shifted. At the highest level of law, homelessness has been officially criminalized. It is open season on eye-sores, and perhaps no issue does more to simultaneously portray both the new heights of American abundance and the scornful nadir of our togetherness.

But, in the words of John Adams, “we must take care, lest borne away by a torrent of passion we make shipwreck of conscience.” For if we aren’t careful now, American lawmakers, employers and prisons will find themselves teaming up once more. They will take a page out of our past and begin leasing out homeless-turned-free-laborers once more. And we don’t want that weighing on our souls, do we now?