How Many Cups 33: Labor Day & The Battle of West Virginia

arguably the most neglected part of American History

A Cup While Relaxing

Sorry for the wait, I was ramping up for the school year. Plus, no one wants their inbox flooded during the waning days of summer. Thanks for the new subscribers, too!

“History is written by the rich, and so the poor get blamed for everything.” - Jeffrey Sachs

In theory, I understand the obsession with battle history. Everything seems to boil down to a series of individual decisions. What if George Pickett never signaled his charge? What is the Nazis didn’t take the bait at the Pas de Calais and doubled down on defending Normandy?

But much of military history boils focuses on the counterfactual. We study minute instructions and tactics to muse over what might have happened differently. Yet, there is a military history in America that intertwines with labor history, and it is hardly ever discussed. How is it that the largest battle in America since the Civil War, one which featured 10,000 armed West Virginians, is not taught in schools throughout the nation?

“While we are fighting for freedom we must see, among other things, that labor is free.” - President Woodrow Wilson, 1917, to the AFL

Our story begins as World War I does. Although its successor was known for pulling America and much of the world at large out of a global depression, The Great War also drastically shaped labor relations in our country.

Specifically, a glut of workers was needed to produce wartime materials, making labor a competitive market. Unions grew more tense as new employees found jobs. If union bosses did not hurry to bring these new workers into the fold, then business owners could take advantage of a fractured laboring class. Plus, the influx of more workers would only drag wages down as the supply of human capital expanded.

Being the literal fuel for such wartime production, the coal industry found itself at the center of attention. Mining towns were often company towns - shanty communities that paid miners in vouchers only to be spent at the company store. Additionally, owners often forced workers to sign yellow dog contracts, which banned them from joining unions and thrust upon them a penalty of losing their company home. If there was ever a time to strike, it was now.

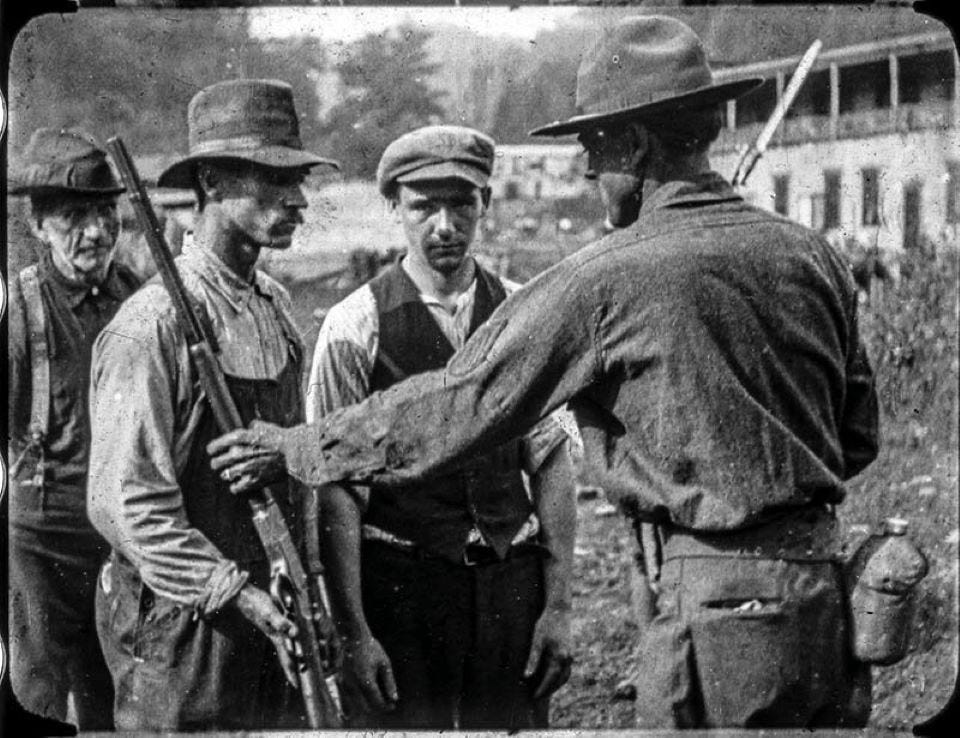

To sniff out potential union movements, company owners hired Pinkerton Agents. Many times these detectives came from military or police backgrounds. Indeed, they were sometimes sworn in as constables or sheriffs, providing them with the power of the law during their anti-union crusades.

“And then, Felts shot the mayor” - Sid Hatfield to U.S Senate

The location for the strike had to be Matewan, West Virginia. It possessed a holy trinity of governing officials friendly to local miners: the mayor, sheriff and police chief Sid Hatfield. Indeed, the chief was much lauded by workers and was instrumental in keeping Matewan one of the few towns not fully dominated by mining bosses. Moreover, Matewan had about 3,000 miners willing to unionize.

Once word spread about this attempt, the mine owners sent agents to evict potential union threats from their homes, weaponizing yellow dog contracts to do so. Hatfield attempted to stop this calamity and directly challenged the authority of the agents to do so. A back-and-forth ensued about the legality of the warrants presented to evict the workers, and the mayor of Matewan was murdered, leading to more gunfire. The moment became memorialized as the Matewan Massacre and sparked one of the nation’s largest armed Civil conflicts.

“Medieval West Virginia! With its tent colonies on the bleak hills! With its grim men and women! When I get to the other side, I shall tell God Almighty about West Virginia!” - Mother Jones

Naturally, the state and local government aided the mining company, not the workers. Sid Hatfield was tried in court for his role in the massacre, having admitted to shooting the Felt brothers who operated the agency in charge of evicting laborers.

But law does not prevail where guns and grudges meet. In May of 1921, Hatfield journeyed to Mingo County courthouse to stand trial for his crimes. There, Felt agents ambushed Hatfield on the courtroom steps and shot him down, in front of his wife, no less. At this point, there was no going back for the union workers.

Still, the union movement needed a leader. Bill Blizzard took the helm, a radical miner who masterminded the union pushback. Under his leadership, miners raided company stores for supplies and weapons, which included a gatling gun (primitive machine gun.) Some 9,000 miners then marched towards anti-union forces at Blair Mountain, wearing red bandanas and popularizing the term redneck.

“These are your people. I am going to give you a chance to save them, and if you cannot turn them back, we are going to snuff them out like that.” - U.S General Harry Bandholtz to union leaders, 1921

The federal government had no room for working class dissenters, sending general Harry Bandholtz to West Virginia in 1921 to quell the miners. He represented the national army and sent a clear message to the unionizers, who had began building encampments and homemade bombs.

The presence of federal power likely emboldened both company owners and whichever police chiefs they had in their pocket. While attempting to arrest union workers in Sharples, West Virginia, a battle broke out. Miners and sheriff Don Chafer’s men exchanged gunfire, only for some innocent women and children to be killed. The already murderous tension was now at its zenith. The battle was underway.

At Blair and Crooked Creek, each side had dug trenches and enforced them with machine guns. Thousands of miners tried flanking the police and company forces but were unsuccessful. Nail bombs and chemical gasses were dropped from private airplanes hired by the mining company. Eventually, military airplanes flew over the battle zone, signaling that federal powers were about to be implemented against the workers.

The battle lasted three days, with miners realizing they could not withstand federal forces. After observing the behaviors of the mine owners, even General Bandholtz would change his allegiance. Yet, the fight continued on, taking place in the form of legacy and impact.

“Their minds and lives are fully occupied with the struggle immediately at hand…teachings and propaganda are directed almost solely against the coal operators of the State, rather than capitalistic interests everywhere.” - Historian Roger Fagge

Precisely once the battle had ended, mine owners began linking workers to radical socialist movements. Yet, both the FBI and federal government denied such claims. Nevertheless, attaching unions to ideals antithetical to America was a smart strategy to discredit union workers and set the public against them.

The miners, however, did not oppose capitalism. Indeed, they saw themselves as willing capitalists who wanted a blue collar chance at achieving the American Dream. While marching away from the defeat at The Battle of Blair Mountain, the miners donned American paraphernalia and carried the flag.

But the damage was done. In the preceding decade, union membership for miners in West Virginia dropped precipitously. Coal company owners continued to suppress calls for better wages and conditions, gaining leverage as coal demand plummeted after World War I concluded.

Yet, the battle remained popular in the nation’s memory and it was called up to help the growth of unions during the Roosevelt Administration. Today, the United Mine Workers of America union is regarded as one of the most influential to ever exist, notably lending their services to steel workers in their question for better conditions.

The Labor Day you’re celebrating was made possible through bloodshed, and a bit of poetic justice. Bill Blizzard stood trial for treason at the very same courthouse abolitionist John Brown did. Yet, Blizzard would meet a different fate, being acquitted of his charges. Keep this in mind today.