How Many Cups 34: That Time New York City Almost Joined The Confederacy

through a Copperhead Mayor

A Latte

I’ve been debating whether or not to disclose that the creator of Central Park also led New York City’s pro-Southern delegation during the Civil War. Such a notion would put Progressive warriors into a soul-searching pretzel.

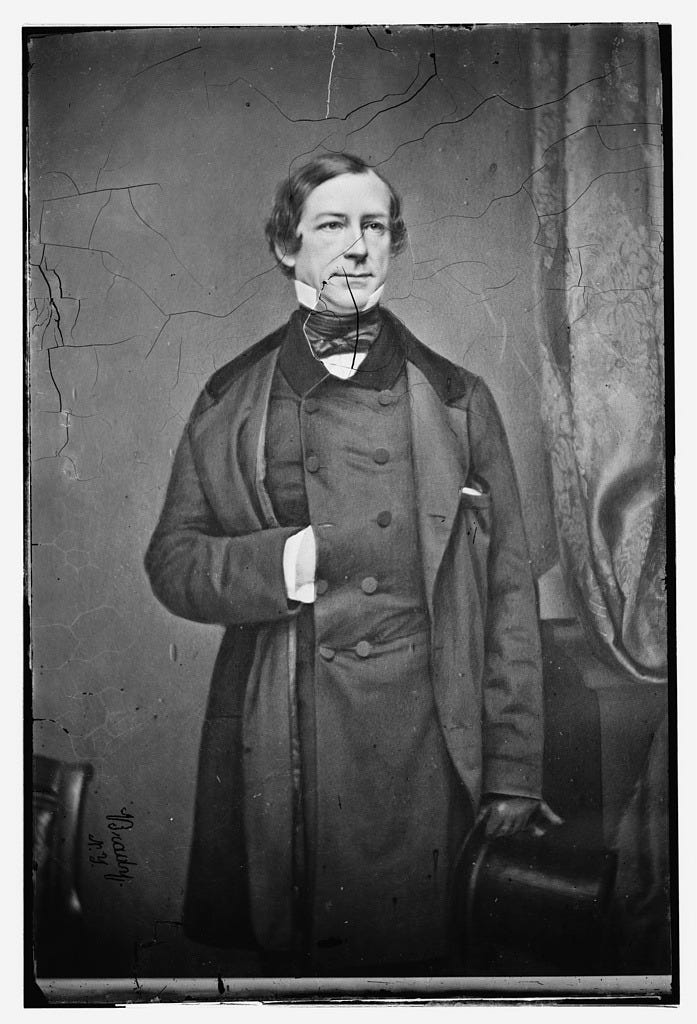

But back in 1860, Fernando Wood did such a thing, likely in support of Wall Street financiers and businessmen alike who depended on the South’s profitable agriculture industry. Of course, upending the region’s access to free labor would disrupt the cash flow back East, making opposition to Abe Lincoln an easy choice.

“With our aggrieved brethren of the Slave States, we have friendly relations and a common sympathy. - Fernando Wood, 1861.

A city of immigrants, hundreds of thousands of New York residents worked back-breaking jobs along the city’s shores. Irish immigrants were known to labor amongst the docks, hauling goods into the boroughs that were shipped north from southern depots.

These immigrants understood that they were directly competing against African-American laborers. An influx of freed slaves, who would sensibly seek to escape the prejudice of the South, would only drive wages down and create more instability for recent arrivals from Europe.

The mayor of New York felt the pulse of immigrant concern and their growing opposition to Lincoln’s efforts. Moreover, notions of a draft were developing, leaving residents to wonder if they’d have to jeopardize their lives only to find the people they fought for competing for their jobs. Such panic allowed Wood to spring a ground-up rationale for opposing the war, although his allegiances may have truly lied with New York City’s elite business class.

“Amid the gloom which the present and prospective condition of things must cast over the country, New York, as a Free City, may shed the only light and hope of a future reconstruction of our once blessed Confederacy.” - Fernando Wood, 1861.

The Free City of Tri-Insula doesn’t exactly capture the urban charm reminiscent of the Big Apple. Nonetheless, Wood proposed that Manhattan, Long Island and Staten Island join forces and secede in their own right. Why? To “make common cause with the South” of course.

His idea was not only proposed to City Council, but adopted as its official policy. Indeed, the sentiment prior to the first shot at Fort Sumter, revealed, according to historian John Strausbaugh, New York to be “the most pro-South, pro-slavery city in the North” due to its “ long and deep involvement in the international cotton trade.”

A combination of working class immigrants and wealthy corporatists applauded the plan, although it was never fully put into place. Regardless, the city was set for an anti-Union explosion, one which only needed a spark.

“With profound regret I have been notified that a conspiracy has been concocted, having for its object the destruction of public and private property in our county, should our Government persist in enforcing the draft.” - Sheriff of Ulster County, New York, 1863.

According to the dustiest edition of Reader’s Digest found in my local library, Wood and company did indeed formulate a secret plan to secede from the Union. The attack on Fort Sumter, however, slammed shut that possibility, as the North grew closer after the Southern attack.

Still, New York City would be plagued by unrest. The 1863 Enrollment Act forced a number of Americans to join Union forces. Incidentally, they were largely upset with the wealthy elite, who had the option of paying their way out of service. They also rebelled against fighting for folks who could presumably compete against them for employment.

The riots left buildings smashed and burned across Lower Manhattan. Police Superintendent John Kennedy was stabbed over 70 times. A number of Black Americans were lynched in the street. What a sad day to be a New Yorker.