How Many Cups 39: Pliny And Marco Polo Discovers Monsters

and no, he did not bring pasta via lo mein to Italy

There is a debate in Roman History regarding hypercriticism versus fideism. Should we trust ancient sources and search their stories of myths and monsters for usable metaphors, or should we disregard such silliness entirely? If we would not trust our neighbor if they told tales of three-headed dragons, then why would we hold antiquities historians in such esteem?

There is a storied legacy of some of the most notable ancient historians discussing all sorts of fabricated beasts. Herodotus, nicknamed The Father of History, even discussed the sphinx had “taken it as true from the Scythians” that the griffin did indeed guard Egyptian gold. What have other famous sourcemakers said about such monsters?

"And I assure you all the men of this Island of Angamanain have heads like dogs, and teeth and eyes likewise; in fact, in the face they are all just like big mastiff dogs.”

- Marco Polo, 1294

The Andamanese are an indigenous people located in the Bay of Bengal towards the Southeast. For over a thousand years they have essentially lived in isolation, gathering and hunting their way towards existence. When an outsider broaches their territory, however, they may never return. Indeed, a visitor from Alabama was shot down by their arrows only a few years back.

Yet Marco Polo was able to write about them in his travel logues during the 13th century, despite there being no evidence that he actually traveled to the region. According to him, the sea between India and Andaman is so treacherous that it can uproot trees and drag them back into the ocean.

Still, Marco Polo claims to know much about the Andamanese. A trader by, well, trade, he focused on their variety of fruits and fleshes, of which the Andamanese have many, Apparently, they truly love the flesh. Marco Polo relayed how the Andamanese would eat flesh of all kinds, even human. Perhaps this is why he declared, with fervor, that the Andamanese possess the head of a literal dog, with the teeth to go with it. But there were more frightening monster along his travels.

“…the Arimaspi are said to exist, whom I have previously mentioned, a nation remarkable for having but one eye, and that placed in the middle of the forehead. This race is said to carry on a perpetual warfare with the Griffins, a kind of monster, with wings, as they are commonly represented, for the gold which they dig out of the mines.”

- Pliny the Elder

Through his works, Pliny the Elder paved the way for his son to achieve something of a life of luxury, as evidenced by junior’s vacation stay near Pompeii during the time of the eruption. One of his most famous publication is his Natural History, in which the Elder mentioned as types of fantastical beasts.

I could focus on the cyclops or the Ophiogenes, who could, “by their touch” heal people bitten by snakes. Instead, I’ll emphasize the Anthropophagi; a man-eating population situated east of the Caspian Sea.

The Anthropophagi frightened Pliny, and for good reason. The were alleged to be “in the habit of drinking out of human skulls” but not before using the still attached hair as a napkin of sorts. Such a description inspired even Shakespeare, who mentioned the race in Othello.

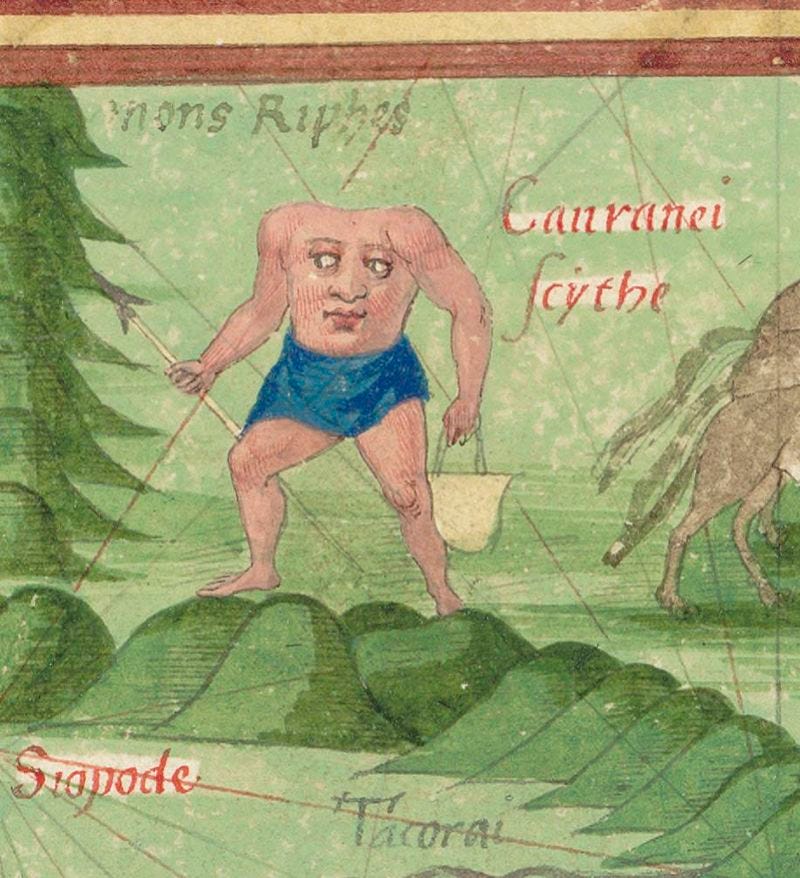

But Pliny also discussed the Blemmyes, which has an interesting connection to Marco Polo. According to Pliny, the Blemmyes had no heads for the Anthropophagi to feast upon. Rather, their “mouths and eyes” were “seated in their breasts.” This must have been particularly frustrating for these peoples, considering they were not a fictional race at all. Rather, they occupied a land near the nile and had a colorful culture.

The concept of headless men is a familiar one throughout History. Travelers from Herodotus to Strabo, Aeschylus to Solinus all mentioned this fictional breed. As did Marco Polo, who stated that the Blemmyes could be found in India, along with other invented humanoids.

What are we to do with such silly notions? Perhaps it is better to try and comprehend why humans have a predilection for the unbelievable. The lesson to be learned is not one about trusting ancient historians. Rather, it is about remembering that humans, in attempts to reach notoriety, may fabricate wondrous myths just for a chance at becoming legendary.