Three Better Ways To Understand Black History

for teachers, but we are all teachers, aren't we?

“The very ink with which history is written is merely fluid prejudice.”

Mark Twain

Think back to your days learning History, whether it be sixth grade or senior year. Perhaps in grade school you made a diorama for Martin Luther King day. As a sophomore you picked up the second half of U.S History, from Reconstruction forward. Depending on which part of the country you were living in, you might have just finished learning about The Civil War or The War Of Northern Aggression.

Teachers, of which I (barely) am one, have overwhelmingly been feeding our students, for decades, a cookie-cutter, palatable version of Black History. Sure, the figures and fact have all been presented neatly. Frederick Douglass. Homer Plessy. Ida B. Wells.

This education, however, was poisoned at the well, and every drink we gulp down does more to remove us from an ugly truth than than it does to confront it.

To come are three cornerstone lessons of American history, each one being currently taught from a foundational standpoint as inaccurate as it is dishonest. If we are to move forward, and towards, a real era of racial equality, we must overhaul entirely the framework in which this history is conceptualized and taught. I’ll frame each example as a question that both ourselves and future generations must reckon with.

“And the rockets' red glare, the bombs bursting in air.”

The Star Spangled Banner

Question 1: If it’s revolutionary, then why is White violence celebrated while Black violence debated?

Two years prior to his famous Dream Speech, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr visited Dickinson College to provide a preview of his most famous remarks. The symbolism was glaring. The institution is named after Founding Father John Dickinson; a prominent colonist who sharply advocated for a peaceful path towards reconciliation with the British during the Revolution.

Dickinson’s Quaker-brand of nonviolence had it twists and turns. Indeed, after the catalytic battles of Lexington and Concord, the “Penman of the Revolution” let all know that he wanted to avoid war with Britain. Three day before America’s first 4th of July, the Pennsylvanian published A Speech Against Independence.

Yet Dickinson still called for drastic changes, and ones without violence. Then he drafted the Articles of Confederation and perplexingly co-wrote The Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms almost a full year before Jefferson authored the Declaration.

Nevertheless, when Dickinson is discussed in History classes nationwide, he is painted as a troubled figure who never fully plunged into the Revolution. When Ben Franklin warned the Declaration’s signers that they must “all hang together” before they all “hang separately” Dickinson was not included in that group, considering he objected to putting his name on the document.

He understood greatly the ramifications of opposing independence and, of course, war. During his speech against the signing, Dickinson wrote, “My Conduct, this Day, I expect will give the finishing Blow to my once too great, and too diminished Popularity.” The sentiment towards violent opposition was growing and Dickinson firmly swam against the current.

He foresaw the destruction of American villages at the hands of the mighty British: “The War will be carried on with more Severity. The Burning of Towns, the Setting Loose if Indians. on our Frontiers has not yet been done. Boston might have been burnt.”

Still, the Declaration passed and Dickinson obliged to command a militia unit during the war. In spite of this, Dickinson’s utility in understanding the Revolution comes in shining a light on the forces opposing violent independence. He represents a little celebrated or studied fact in American History: the colonists had to be convinced to fight against the British.

Or, framed more accurately, a subset of underprivileged demographics - women, propertyless white men, slaves and freedmen - had to be convinced by comparatively wealthier white men of status that risking their lives for said propertied men was a worthy cause. The men who held pens instead of swords were beseeching the less fortunate to die for them, and in doing so transform Liberalism from thought-experiment to actual experiment.

This is the proper, more Truthful telling of the American Revolution. It is, however, rarely depicted in either pop culture or patriotic celebration. Rather, we digest songs, movies and historical reenactments every Independence Day that suggest the entire nation was on board with battling the British. That violence was not just the only way forward, but the only justified way forward. That political revolution and violence were, at least at the time, tautological - one could not be had without the other. One is the other.

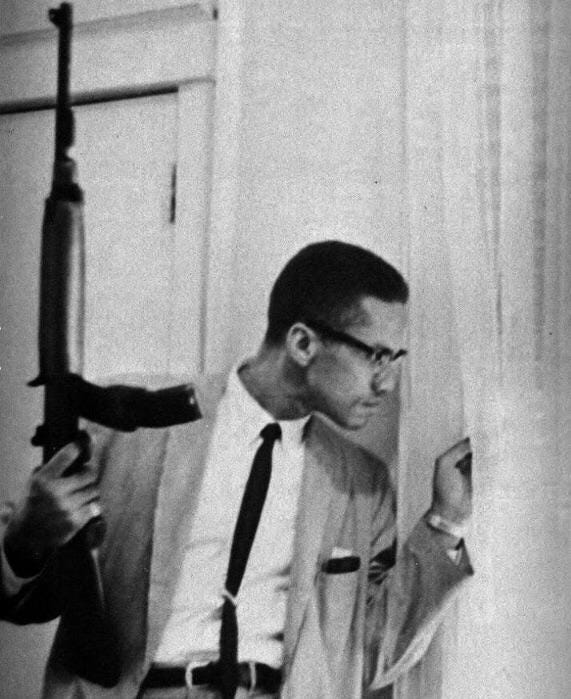

Juxtapose this to the classic high school debate pitting Malcolm X and Martin Luther King against each other. It is common practice nationwide to pair The Ballot or the Bullet with Letter from a Birmingham Jail and then task children with arguing for one strategy or another. This usually yields an essay or classroom debate centered on the following: was violence (Malcolm X) or nonviolence (Martin Luther King) the best method for achieving equal rights?

The question is ludicrous and must be rejected wholly in order to truthfully comprehend the way in which Black History, and by extension Black People, have been held to a higher standard than their white forebears, even when fighting for the same causes.

Why is this question not asked of our Founding Fathers? To be sure, there is a plenty of evidence that deploying a violent rebellion was debated at the time of the Revolution, as well as after the fact. Why is this evidence not collected, disseminated to students and then used a source material for the same question we ask of Malcolm X?

Mercy Otis Warren wrote a myriad number of letters to John Adams debating the merit and ramifications of violence, often arguing for patience and peace. By 1835, De Tocqueville was forecasting the damage that can come when tyranny of the majority is disguised as a will of the people, especially when springboarded through violent means, which undeniably constitutes our nation’s genesis. Adam Smith proposed the concept of “savage patriotism” in which a nation will perpetuate bloodshed if and when it fails to perceive themselves as a movement extending beyond homeland and to all mankind. And of course, there was the aforementioned debate that happened on the goddamn floor of Independence Hall during the making of the Declaration.

In short, there is no dearth of debate evidence over the use of violence to break away from the tyrannical British. Still, nonviolence has not been levied upon our founders as a standard we should at least consider holding them too.

For Malcolm X, and other Black leaders, however, nonviolence was the standard. What’s worse, there is more evidence that the American government was methodically deploying violence as a tactic to keep Black folks from their civil liberties than there was the British doing the same to colonists.

There was not an average of one colonist lynched every week during the Revolution. The British were not stringing colonists to trees, drawing the scene and then sending those drawings as postcards to friends. It was only after the Declaration - an act each signer understood to be an invitation of war - that the British responded by using military force and hunting the rebellion’s leaders. Remember, the trial of the Boston Massacre found the British troops not guilty and they were defended by none other than John Adams.

Yet, all of those actions happened to Black folks. J. Edgar Hoover, with the tacit approval of Attorney General Robert Kennedy, encouraged Dr. King to commit suicide by sending to his wife a recording of him having an affair. Famed historian Manning Marable found it more likely than not that the FBI played a central role in Malcolm X’s death. Chicago police broke into Fred Hampton’s house at 3am and killed him in front of his girlfriend, who was carrying their child. Senators campaigned on personally attending to lynch mobs. Nixon and Reagan can be heard on tape calling African people monkeys, subjecting them to a subhuman form consistent with their America history.

If race was removed from the equation, every signer of the Declaration would support Malcolm X. The American government, locally and federally, was conspiring to kill Black leaders who wanted nothing more than the same liberties the founders fought for. Please, stop asking high school students to debate the merits of violent versus nonviolent resistance. This, my dear readers, is the epitome of White privilege.

White folks have the permission to be violent when pursuing ideals they believe trace back to their country’s origin. After that, we have the privilege of formulating a history on the violence, one which is falsely justified and therefore weaved into the grand American story through mass dissemination.

When J6ers stormed the Capitol Building with zip ties and an assortment of weapons, they were pardoned. When Malcolm X called for “using violence in self-defense” he was murdered. Let’s honor him by remembering the second half of that dictum: “I don't call it violence when it's self-defense, I call it intelligence.”

Which brings us full circle, back to the quote which began this section. The song crowning America’s genesis is as violent as it is patriotic. The Black National anthem, however, offers no such imagery. There is no battle to be told of, no bombs overhead. Just the “blood of the slaughtered” who weren’t afforded the same ticket into American acceptance: the chance to fight for freedom and be revered for it. In sum, the chance to be fully American.

“The civil rights movement circulates through American memory in forms and through channels that are at once powerful, dangerous, and hotly contested.”

Historian Jacqueline Dowd Hall

Question 2: Have we misnamed the Civil Rights Movement? Why would that be dangerous?

The science of making history is called historiography. One of its tools is periodization; the art of identifying and naming eras for certain moments in time deemed meaningful and therefore, teachable.

There is a debate amongst historians about what dates should constitute the era or eras of Black History, and what names they should be called. There is the “Long Movement” theory, suggesting that the Civil Rights Movement did not suddenly spring to life when Rosa Parks refused to change her seat. Activism throughout the 1930s and 40s is connected to the rise of King and X. This is also known as “the movement of movements.”

I have my own theory.

The best and most truthful way to teach the Civil Rights Movement is rarely, if ever, seen in classrooms. Extend that sentiment to the other periodized Black eras: the Enslavement Era (pre-Civil War), the Reconstruction Era (post-Civil War), the Great Migration (early 20th century), and the Harlem Renaissance (1920s.)

The very naming of these moment as eras inserts a line of demarcation between all of them. It leaves the learner no choice but to intuit that those eras have beginnings and endings. It is purely logical for the learner to then believe that each era must have had its own unique propellant and conclusion.

This does more to silo Black History into separate, disconnected narratives than to present it as an interwoven struggle that marches forward through time. If it isn’t dripping through the screen yet, what I’m arguing is that American historians have failed to accurately categorize the plight of Black folks in this nation, making themselves in part responsible for the inability of the country to reconcile its original sin.

In our opening question, I danced around a historiographic question: why is the Black struggle for civil liberties treated different than the White struggle for them? This is because the colonists’ battle for rights was and is dogmatically categorized as revolution. Contrast that with the Black fight for those same liberties. Those eras are given odd or even poetic names like Migration or Renaissance.

How disgraceful. I’ll tackle the Revolution issue in a moment, but first consider moments of White migration versus Black migration. In the 1840s White settlers moved West to expand slavery and claim land. In doing so they genocided Native Americans and fought a fellow sister democracy (Mexico) to steal their territories.

We’ve labeled this Manifest Destiny, impressing upon learners that White migrants were more saintlike than savage. Contrast this with The Great Migration; a time when Black folks fled the South to avoid lynch mobs and forced labor. Despite abstaining from slaughter along the way (and indeed, facing violence when reaching Northern cities) Black Americans were not afforded the same divine lionization their migrant counterparts were.

The reason Black leaders during the Civil Rights Movement were held to a standard of nonviolence is precisely because their plight is not defined as a Revolution. To educators and historians, it seems as though revolutionizing - the act of overthrowing a dogma or paradigm to usher in foundational change - is the skeleton key unlocking violence as acceptable.

But what is the Black struggle if not revolutionary? There is and was, definitionally, a dogma they fought against. For hundreds of years in America relegating Blacks to second class citizens, or something worse, something subhuman, was established principle. Legally, judges and elected officials defined them as such. Socially, the violence and weaponization of discrimination concludes that too. The standard in America was to keep Black folks anything but American.

What’s more, African-Americans were fighting for the same privileges and rights guaranteed by our Constitution that White colonists fought for, people we literally call Revolutionaries. If each demographic were fighting for the same paradigm-busting ideals and each demographic upset the presumed convictions of the time, why is only one struggle coined as a Revolution?

Black violence, even in self-defense, has been deemed intolerable by mainstream education. White violence for the same causes is more than celebrated, it is the source of a national imagination underpinning what it means to be an American. By teaching the entirety of Black History truthfully - as a continuum of both Revolution and the American Revolution - the nation may begin to see the Black plight for what is really is: the American plight.

“White supremacy and white nationalism is not a problem that is harming Black America.”

Provocateur Candace Owens

Question 3: Why are there no Pro-Black leaders today?

Candace Owens is the most popular Black leader today and she is behind the quote leading this section. To be frank, I am not Black, meaning I would not write this next sentence unless I was entirely ethically and historically sure of it. Candace Owens is anti-Black.

Something I always found peculiar was the lack of Black leaders when compared to White leaders over the last 40 years. Do a mental exercise and create a list of effective, durable Black leaders since Jesse Jackson. It’s scarce. Indeed, there is a not a defining Black voice between 2000 and 2008.

I’d even argue Barack Obama is not one of them. While he is undoubtedly an inspiration and figure of generational importance, he is known for everything but advocating on behalf of Black folks. With the exception of a few speeches every other election cycle, Obama has faded into retreat, even during the rise of anti-Blackness beginning under the Trump Era.

What makes this question so interesting is the juxtaposition formed when comparing it to White leaders, specifically ones that have a nationalist or ethnocentric tinge. Unquestionably, such leaders have been on the rise. Let us never forget that President Trump began his campaign under the assumption that it is abnormal for Mexicans to not be rapists or thugs. Or that the only president he argued wasn’t legally able to be one happened to be a Black man. Or his Muslim ban. Or his “stand back and stand by” comments to the openly racist Proud Boys.

Perhaps this quote from Justice Department Elyse Goldweber who represented the government when they sued Trump for discriminatory housing in the 1970s:

“What they had done was send ‘testers’—meaning one white couple and one couple of color—to Trump Village, a very large, lower-middle-class housing project in Brooklyn. And of course the white people were treated great, and for the people of color there were no apartments. We subpoenaed all their documents. That’s how we found that a person’s application, if you were a person of color, had a big C on it.”

Regardless of your thoughts about Trump, his orbit is undeniably full of White Supremacists who offer their support at every turn. When the uber popular Nick Fuentes is not denying the Holocaust, he is meeting Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago. Former Trump mentor Steve Bannon produces a podcast which garners millions of listens daily; a program which lacks no shortage of White nationalist ideals. In addition to the uprising of these leaders, the SPLC noted that “165 active white nationalist groups” exist in the States as of 2023, their highest recorded number in history.

There is not, however, an equal force of Black leaders pushing against voices of hate. This is a peculiar mystery and a sharp break from a rich American tradition. How can the nation usher in the largest civil rights protest since Dr. King was alive without a national figure emerging? How could the George Floyd protests not produce a leader? Compounding this question is the advent of social media, which seemingly churns out stars overnight for everything but Black advocacy.

While I am not a fan of her academic scholarship, most of which was cogently refuted by the country’s greatest living historians, Nikole Hannah-Jones was undeniably silenced. Her 1619 Project was received with so much backlash from conservatives that they rallied Hannah-Jones’s employer, the University of North Carolina, to deny her tenure and by extension, her very job. Disallowing a professor the chance to speak freely about their beliefs is hard to describe as anything other than silencing.

Hannah-Jones moved on to Howard University, where the best writer since James Baldwin, Ta-Nehisi Coates, joined her. He, too, has been treated as an unwanted, unmerited voice in America. Coates is a fighter for marginalized people everywhere and attempted to extend his services towards the Palestinian plight. How was he greeted?

CBS News’s Tony Dokoupil interviewed Coates and asked with his first question: “What is it that so particularly offends you about the existence of a Jewish state?” This line of question was so assumptive, so journalistically inappropriate that even CBS had to chastise its star host. Moreover, it represents a form of suffocation. Instead of being able to discuss in detail the depths of his new book and all of Coates’ views on modern discrimination, he immediately had to defend a bogus claim of anti-Semitism. A conversation which could have vaulted him further into Black leadership was stemmed at the beginning. He was put on defense when anti-Blackness needs an attacking voice.

Something is happening at our elite institutions. Ibram X. Kendi was forced to flee to Howard after he lost funding at Boston University. Cornel West, who would have become the smartest person ever to sit in the White House, ran for president in 2024. His press coverage was scarce, despite advocating a policy platform of populist ideologies. Robert Kennedy Jr, in contrast, was constantly platformed by major networks despite similar polling numbers in the single digits.

From 30,000 feet, it is apparent that White supremacists have no dearth of vocal, popular mouthpieces. Ask yourself, however, where their counterparts are? If they are not quivering in the shadows - which they are surely not - then why aren’t they just as popular? Why have they not been platformed?

I have ideas, all relating to what content algorithms find attractive and addictive. But I do not have a definitive answer I am comfortable sharing. What I will do, however, is ask teachers to pose this question to their students and just a importantly, themselves.